The project held its third international conference on 16–17 May at the Institute of Historical Sciences in Dubrovnik. The conference titled Early Modern Diplomacy across the Religious Divide: Justification, Defamation, Obfuscation, and Misapprehension welcomed researchers from several countries to discuss how early modern authors, diplomats and other political actors thematized relations between state and non-state actors of different religions or confessions.

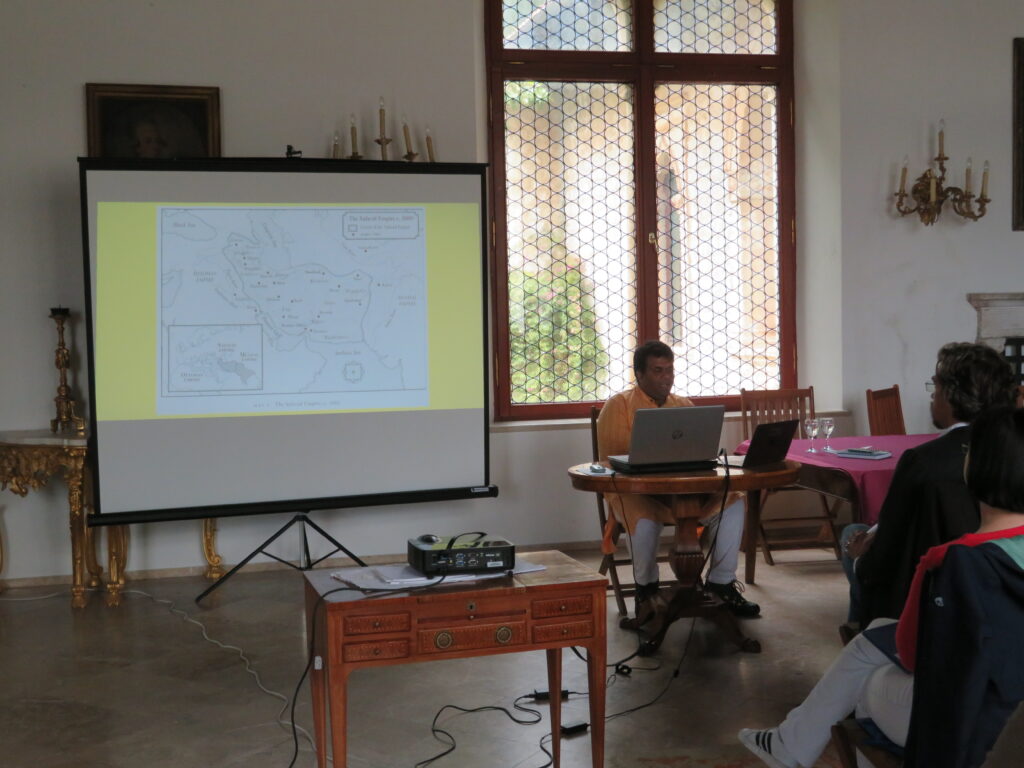

The first panel’s broader topic was how entities communicated about and represented their connections with the religious Other. In the first paper, Isabella Lazzarini analysed the shift in interactions between the Italian city-states and Islamic rulers, following the fall of Constantinople. Rubén Gonzalez Cuerva explored how diplomatic relations with Muslim entities were communicated, represented, and reflected upon through pamphlets and manuscript sources in the seventeenth century’s Spanish Monarchy. Habib Saçmalı’s paper focused on the Ottoman Empire’s attempt to communicate and legitimize their actions regarding the civil war in early 18th-century Iran, and their support of the Shiʿite Safavid prince in place of the Sunni Afghans.

The second panel was concerned with the uses and abuses of religious discourse. Shounak Ghosh focused on how a ruler from western India beseeched the help of the Ottoman sultan against the Portuguese in the early 16th century, using wording and discourse in his correspondence that was focused on the religious aspect of the conflict. Lovro Kunčević presented the measured way in which the Republic of Ragusa communicated with both its Eastern and Western neighbours, carefully balancing the two sides’ interests by applying keenly perfected communicational formulas for excusing any and all of the Republic’s actions. Natalia Królikowska-Jedlińska’s paper dealt with the Crimean Tatars and how they presented their religious identity in their diplomatic dealings with different entities.

The third panel’s main characters were the diplomatic mediators, who worked across the religious divide in different settings. Francesco Caprioli’s case study of a Spanish envoy explored how pervasive mistrust figured in the cross-confessional diplomacy between the Spanish Habsburgs and the Ottoman Empire, and how an individual could wield it in their diplomatic missions. Bastien Capentier examined a group of Genoese merchants, serving as intermediaries and effectively the covert agents of the Hispanic Monarchy at the Porte. Using diplomatic correspondence and reports, and focusing on the case of a Morisco envoy in Venice, Yunus Dogan outlined the details of Morisco-Venetian inter-religious diplomatic relations.

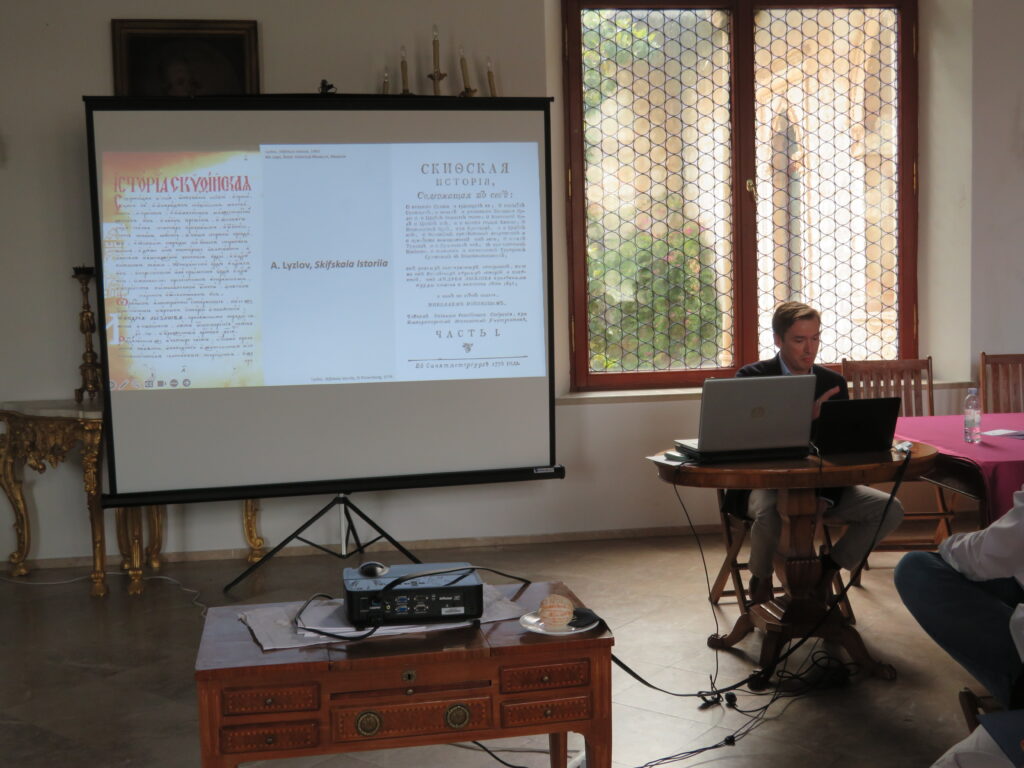

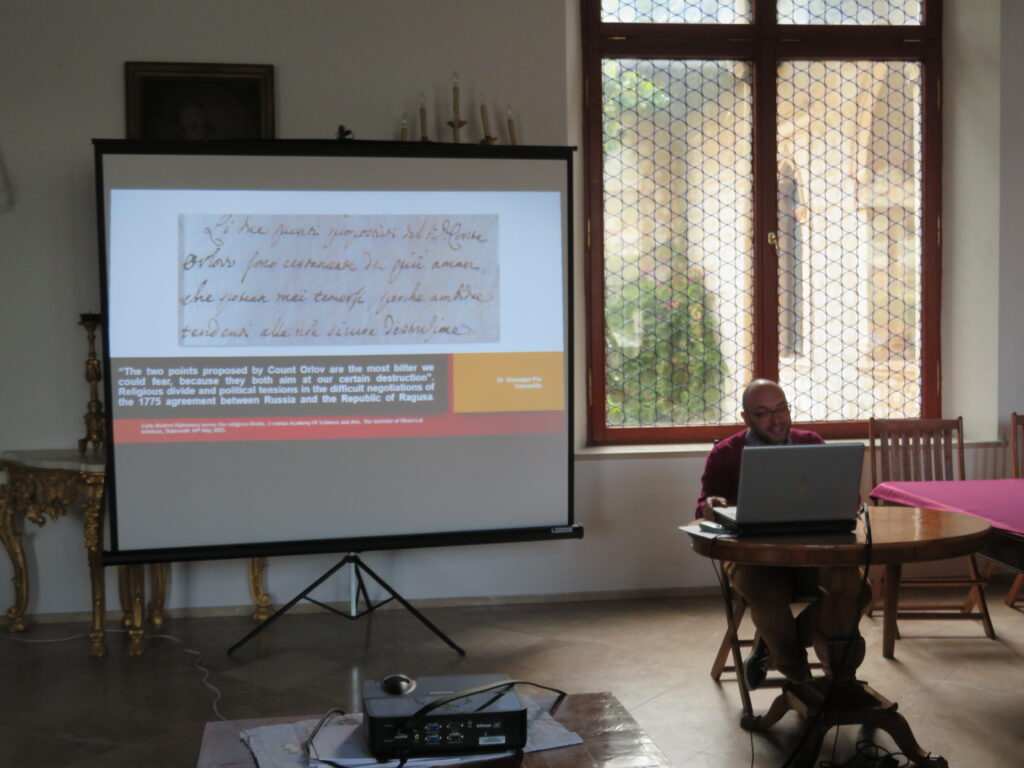

In the closing panel of the first day, presenters detailed their research on negotiations bridging the religious divide. Jan Hennings introduced the Russian-Ottoman diplomatic relations at the beginning of the 18th century, using the documents provided by the ambassador Peter Tolstoi, and other related sources, he also focused on the role of the Republic of Ragusa as a mediator between the two empires. Ragusa’s position towards Russian relations in the 18th century was also treated by Giuseppe Pio Cascavilla, who focused on the establishment of a Russian consulate in the Republic and on the potential threat the Ragusans perceived the arrival of the orthodox diplomat, and all that would follow. Hüseyin Onur Ercan focused on the grand ambassador of the Porte in Vienna, and how he regarded and disregarded protocols and traditions based on his religious differences.

The first panel on the second day addressed the discourses of peace, cooperation, and tolerance across the religious divide. Zsuzsanna Hámori Nagy outlined how John I of Hungary tried to position his country in the shadow of both the Ottoman and the Holy Roman Empire. Laura-Sophie Stolzenberg examined how a Protestant author urged intra-Christian tolerance in order to face the Ottoman threat of the era, and how her poem constructed the religious otherness of the Muslims. Konstantinos Poulios detailed the new attitude (and, in addition, its historical roots) that the Ottoman Empire professed towards the idea of peace-making with its Christian and Shiʿite neighbours.

The following panel focused on the small players between Ottomans and Christians. Zsuzsanna Cziráki focused on the Transylvanian Saxons and how they as Lutherans interpreted their alliances formed with the Ottoman Empire and the Catholic Habsburgs. Michał Wasiucionek concentrated on Polish-Moldavian relations in the first half of the 17th century. He detailed how the Moldavian voivodes represented and explained their diplomatic connections and dealings with and to the Porte. Gábor Kármán outlined the discourses surrounding the question of Ottoman vassalage and the discussions at the Transylvanian Diet of 1685.

The final panel opened more broadly toward a history of literature and scholarship. Johann Nicolai detailed the history of Oriental studies in Dorpat. Eduardo A. Olid Guerrero examined the literary manifestation of the tensions between the Spanish Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire in the writings of Miguel de Cervantes, exploring the cultural and interconfessional connections. Hana Ferencová presented how an English physician and traveler viewed and represented in his accounts the lands bordering the Ottoman threat, and how he interpreted the diplomatic relations with the Ottomans, experienced during his stay in Vienna, towards his international audience, applying his Anglican perspective.